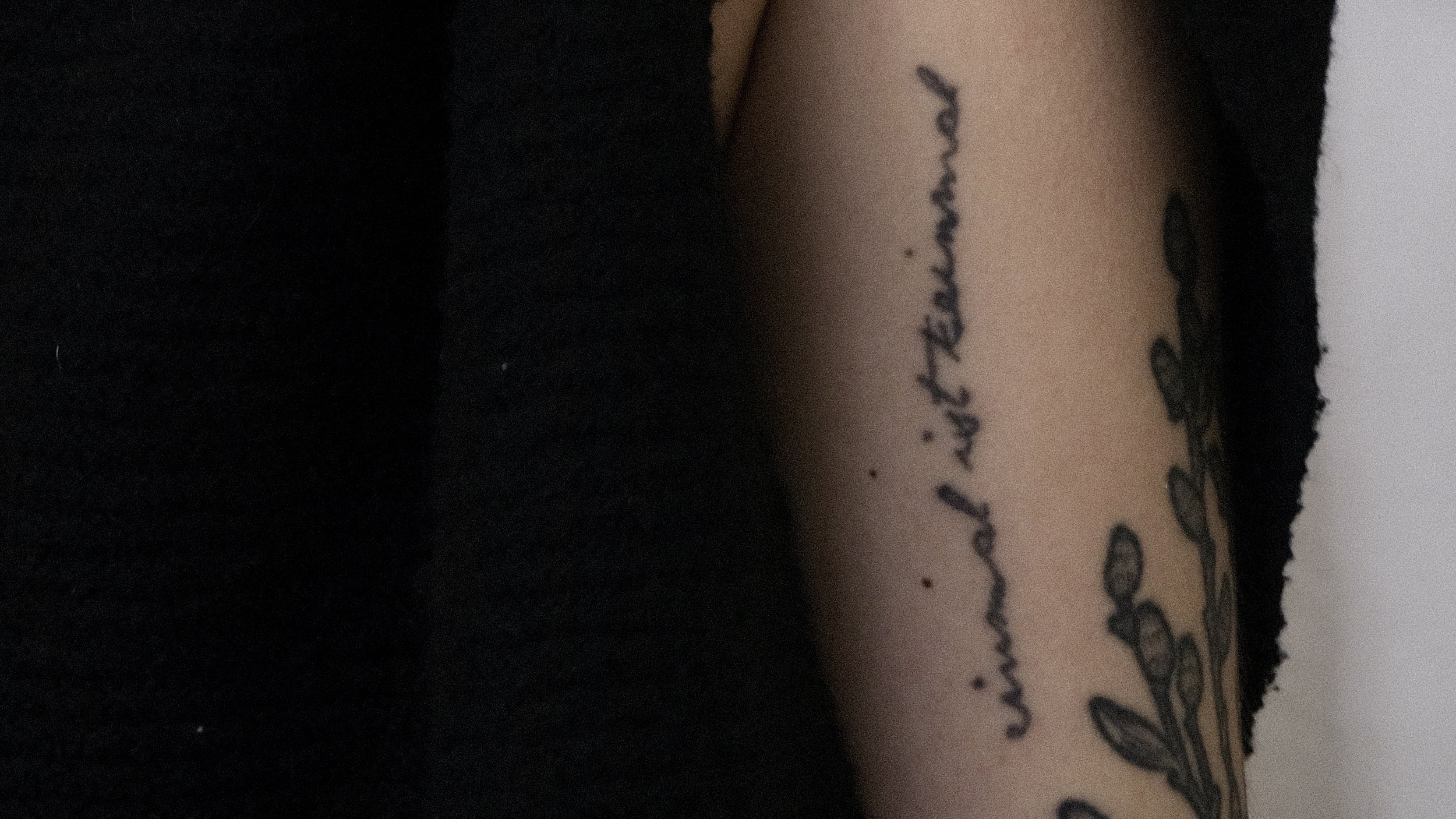

I was nineteen years old when I got “einmal ist keinmal” tattooed in a near-illegible script on the back of my right arm. You could translate it from German as “once is never” — funny, I suppose, for a permanent body modification. The tattoo artist was a trainee and did it for $20 in a dark second floor studio in downtown Halifax a few days after I’d finished Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

I don’t think about this tattoo very often, in part because I rarely see it. I sometimes catch a glimpse of it if I’m shaving my armpits, but then it’s upside-down and I can’t really tell the difference between the freckles and the dotted-i’s. But it’s been on my mind almost daily since Kundera died about a month ago in his Paris apartment at the age of 94.

I was introduced to Kundera by my best friend’s inscrutable older brother, who sat beside me in an undergraduate seminar. As he handed it to me, a ruby red maple leaf swooped silently through the open auditorium window and danced an elegant pirouette before falling to the floor. It seemed like we two were the only people in the whole auditorium who noticed it. It set just the right tone for discovering a writer and novel so generous with symbolism.

There’s no need for me to recount the story here (but do yourself a favour and don’t watch the film — not even Juliette Binoche could save it, and Kundera never gave film rights for his work again). All you need to know is that our protagonist Tomas is grappling with whether a life of freedom is inherently meaningless, and whether a meaningful life is a cage.

“Einmal ist keinmal, says Tomas to himself. What happened but once, says the German adage, might as well not have happened at all.”

Reading these three words — “einmal ist keinmal” — certainly freed me. It shook me out of my preoccupations (I’d been a deadly serious teenager) and showed me another way to live. I was free to experiment in friendship and sex, free to tattoo my body and occupy that body without shame, free to rage and to create and to love, because none of it mattered. It was all wonderfully, blissfully meaningless.*

The nihilistic view that his life and choices don’t matter is the foundation of Tomas’ freedom. He’s estranged from his ex-wife and child, is relieved when his parents break away from him, and has a series of affairs according to his will and desires. With nothing and no one to be responsible for, he’s “enjoying the sweet lightness of being” when his new lover Tereza comes along like “a child put in a basket and sent downstream” and asks him to commit. Suddenly, life threatens to take on meaning like a boat takes on water.

(I won’t go as far as to say I identified with Tomas. There are many parts of his character that are deplorable, sexist, and outright cruel. I recognised much more of myself in Tereza; in an interview, Kundera said “her soul doesn’t feel comfortable in her body.” Her dreams are concerned with privacy, annihilation, and the borders between herself and others. And anyway, Kundera clarifies that both characters exist only to illustrate something: “Characters are not born, like people, of woman; they are born of a situation, a sentence, a metaphor, containing in a nutshell a basic human possibility…”)

I was studying philosophy, so it’s peculiar that Kundera was my first proper introduction to Nietzsche. Although he loomed large on my required reading list, I’m not sure I even opened my Nietzsche Reader. We’d only just finished with Kant, and I was so relieved by the categorical imperative that I didn’t touch anything else for weeks.† Plus, I was highly suspicious of ‘philosophy bro’ types, who appeared to have the monopoly on Nietzsche (and Adorno and Sartre and NPR and summer in Berlin). But literature led me back there in the end. The gift of moral certainty from Kant transformed under Nietzsche into the curse of eternal return, “the heaviest burden,” which Kundera sets up in opposition to “einmal ist keinmal.” In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche writes:

What if some day or night a demon were to steal into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: “This life as you now live and have lived it you will have to live once again and innumerable times again; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unspeakably small or great in your life must return to you, all in the same succession and sequence — even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself…”

It’s worth remembering that the subtitle of Ecce Homo is “How one becomes what one is.” This process of becoming ourselves happens when we wilfully embrace our own choices and the consequences of those choices — whether they are wonderful, terrible, or banal. What’s implied is that by embracing our strong and capable will, we’ll also have the strength to act in a way that our choices are bearable at the very least, even in a hypothetical eternity. The upside of this responsibility is our astounding, god-like capacity to create our lives as we see fit.

But our creative power has a catch. Every decision closes the door on innumerable other possibilities. In the novel’s early pages, Tomas must decide whether to pursue a romance with Tereza (heavy, significant) or continue with his no-strings-attached affairs (light, insignificant). He finds that it’s impossible to choose correctly; there’s no way for him to know what he really wants when he’s lived only once and has nothing to compare his decisions to. “We live everything as it comes,” he thinks, “without warning, like an actor going on cold.” If once is never, then it hardly matters, but if once is all we have and we’d like it to mean something, then it matters quite a lot.

“If eternal return is the heaviest of burdens, then our lives can stand out against it in all their splendid lightness.

But is heaviness truly deplorable and lightness splendid?

[…] The heaviest of burdens is therefore simultaneously an image of life's most intense fulfillment. The heavier the burden, the closer our lives come to the earth, the more real and truthful they become.

Conversely, the absolute absence of a burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into the heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant.”

At the time of my first reading, I was more than happy to be “half real” and as free as I was insignificant, but my ideas have shifted since (and continue to shift). As Nietzsche asks, “Do you want this again and innumerable times again?”, Kundera's characters also shift between lightness and weight, caught in the balance between fleeting desire and the pursuit of something more substantial. Heavy characters like Tereza try in vain to weigh down the lightness of life by burdening it with meaning — politics, human rights and ideals, love. Tomas accepts life’s lack of meaning, yet he stays with Tereza in the end. Why?

Desire and meaning, lightness and weight — these concepts not totally opposed even if we can’t properly reconcile them. A few weeks ago, a dancer friend of mine attended a workshop on jazz improvisation and shared a quote from the Canadian drummer Jerry Granelli‡:

“One reason why people like improvised music is that it’s a direct reflection of life, not something we thought up… makes you think you’re going to die for a moment. Do you have the courage to play?

Can I move out of my desires and into compositional choices?”

Can I move out of my desires and into compositional choices? It’s probably a good thing I hadn’t heard this line until now, or else I might’ve tattooed it, too (though I doubt it would’ve fit on my arm — a leg might do). I like its potential for more than one meaning — moving out of my desires might mean moving away from them, or moving from within them. But it’s not our desires but our compositional choices that make life what it is, and make us who we are (“How one becomes what one is.”). Whether those choices are meaningless or not, it’s true that once we’ve played them, they’ll echo on forever.

Aside from Unbearable Lightness, I always found Kundera’s nonfiction more compelling than his fiction, but I suppose the line between the two was never very clear. No one wrote quite like him. I never knew a writer could narrate that way, jumping from Nietzsche to a dog’s inner life to a bowler hat to artistic kitsch and back again without missing a beat. (And what a narrator he was! Playful. Provocative. Ironic but not unkind. Neither omniscient nor ignorant — an indifferent god waiting to see how man, imbued with free will, might act). In a later essay, he defined the novel as the “form in which an author thoroughly explores, by means of experimental selves (characters), some themes of existence.” Yes, by trying Tomas on, I could experiment with weightlessness for the first time — something philosophy and political thought could never give me.

Merci, Milan, for that.

*That is, until I encountered Levinas and Butler, and ethics brought me back to earth.

† Kant told me that if I was faced with a moral dilemma, all I had to do was imagine that my action or response to this dilemma would apply in every instance. In one way, what Kant implied was that “once is always.” Choose wisely and then let it go, with the relief that you have chosen right. I also have a rather sticky memory of driving a classmate home, a boy who’d written a fine essay on Nietzsche’s ressentiment, and letting him explain all the essential tenets in the week before our oral exams. I was distracted by a delicate-looking freckle just on the outer rim of his ear. My feelings about this freckle account for ninety percent of the memory.

‡ Granelli is most famous for playing drums in the Vince Guaraldi Trio for the peerless soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Christmas.